Resurrection Bear

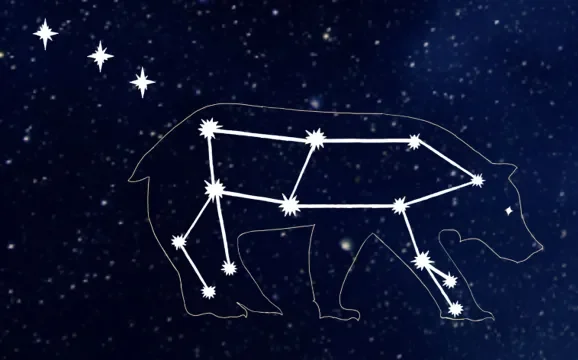

The constellation Ursa Major

There was an obscure holiday recently that you may have missed. The feast day of St. Tiburtius, known in Scandinavia as Tiburtiusdagen, was April 14th. Leaving aside the saint it’s named after, the date is better known as the traditional day when bears are said to come out of hibernation.

In North America, too, bears typically emerge in March or April. Where I live, it tends to be right around now. It also, not coincidentally, is a time when the constellation Ursa Major, the “Great Bear,” is prominent in the night sky. While visible all year in the Northern Hemisphere, Ursa Major’s best viewing is in April.

The most popular myth about this constellation is the Greek version. It tells the story of Callisto, a follower of the hunting goddess, Artemis. Like all the companions of the goddess, Callisto had sworn to remain a virgin for all her life. Zeus had other ideas, however. He had seen her, and as with so many other Greek myths, his libido set the stage for tragedy.

Callisto became pregnant, and when Artemis found out, she was enraged that the woman had violated her vows. As punishment, the goddess turned her into a bear, cursed to live the rest of her life in the wild.

Meanwhile, her son grew up to be a hunter. One day, her son was out hunting when he came face-to-face with a big she-bear, and — you guessed it — the bear was Callisto. Before he could kill the bear, Zeus intervened and swept them into the sky where they became the constellations Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, the big and little bears.

There are other versions of the myth, however, and some far older. It is part of a story complex or “mytheme” known as the Cosmic Hunt. In some of the oldest versions, the stories centered on ungulates, hoofed mammals like the elk or caribou, or going further back, perhaps even woolly mammoths.

But bear myths have become the standard and are especially prevalent in the north. Some Native American traditions, for instance, tell of a group of hunters pursuing a bear. When the bear, represented by the constellation, is eventually caught and wounded, its blood falls to the earth and stains the leaves. It’s said that this is why leaves turn red in Autumn.

The connection between bears and northern climates shouldn’t be surprising, considering that the word arctic literally means “bear country.” While various bear species can be found in places like India, Thailand, South America, and Italy, the north is by far where bears are most prevalent.

And reverence for bears in this region of the planet goes back a very long way. In some cultures, the line between bears and humans becomes blurred. Parts of Scandinavia seem to have held beliefs that bears could be humans in bear form — a belief reinforced by the fact that a skinned bear looks eerily human in shape. The link could also be symbolic. There were areas of Norway where, up until fairly recently, the act of betrothal was referred to as björnas, being “bear-ed,” and the betrothed couple were then referred to as björnarna, “the bears.”

Meanwhile, in some North American indigenous traditions, bears were considered left-handed, a trait associated with healing (also both traits associated with women, by the way). Left-handed people, then, were associated with bears and believed to have shamanistic gifts. Moreover, a person could take on the bear’s characteristic wisdom and healing powers by donning a bear mask or the skin of the bear.

In his influential book The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology, Joseph Campbell theorized that there was at one time a Paleolithic circumpolar bear cult, an idea supported by the fact that forms of bear ceremonialism are found throughout the northern regions of Eurasia and North America.

It has been suggested, in fact, that bears are connected to many early forms of art and spiritual practice. The oldest musical instrument ever discovered is made from the femur of a bear, and humans may have been inspired to make cave paintings by observing the scratches bears left on cave walls.

E.C. Krupp is the world’s leading authority on “archaeoastronomy,” the study of how ancient peoples venerated the skies. Krupp, like Joseph Campbell, points to bears as the inspiration for early shamanistic practices. One of the most distinctive aspects of the shaman’s role was to act as a bridge between the human world and the spirit world, and they did this in part through symbolic dying and rising again in the form of trance. In his book Echoes of the Ancient Skies, Krupp points to the very act of hibernation as the thing that makes bears so spiritually significant.

“Throughout the northern world the bear is an important image in the shamanic tradition, and it is fairly easy to see why this might be so. As a powerful creature, the bear is a natural embodiment of the shaman’s power, but the bear shares another aspect of the shaman’s path. In winter, the bear hibernates. It emerges in spring. Hibernation is a kind of death, and it parallels the shaman’s ‘death’ — the obligatory trance…He is reborn, as is the bear when winter’s death is done. Power and the cosmic cycle are locked in the habits of the bear” (Krupp, p.140).

Bears are the prototype for the dying and rising being, and while today we still associate Spring with bears coming out of hibernation, in the ancient understanding, the causal arrow may have been reversed. It wasn’t that bears woke up because Spring arrived and things thawed out. Instead, bears came out of hibernation and brought new life with them. They make Spring happen.

So, enjoy the warmer weather, friends. Notice the new buds and the little green things sprouting from the dirt. Also, step outside on a clear night and observe Ursa Major overhead. This constellation connects us to the old stories and to the people who told them. It can connect us to bears, too, the sacred beings who represent the resetting of the world, the return of life, the triumph of life over death, and order over chaos.

Spring has arrived. The Great Bear is rising, and the world is resurrecting with it.

Originally published in The New Outdoors