Re-animating our Worldview

Face in tree (AI generated)

I once had the honor of getting to know a man who was a spiritual leader and elder in his Anishinaabe community, part of the indigenous peoples of the northern United States and Canada. We spent many hours together while he was in the hospital recovering from an injury. I was his hospital chaplain, part of the interdisciplinary team caring for him during his healing process. Each Friday I would wheel him into an outdoor area where he would perform a smudging ceremony using sage and tobacco, and then we would spend some time discussing his life, his beliefs, and the state of the world. One day he told me the following story.

“When humans first came into being they were given four tablets, one for each of the colors of mankind. The tablets were engraved with wisdom on how to live in harmony with the land. Today, the tablet for the First Peoples of the Americas is held by the Hopi of the Western United States. For the people of the East, their tablet is kept in Tibet, and Namibia holds the tablet for the African people. But for the white man no tablet exists. It was lost long ago…”

This wasn’t shared out of personal disrespect to me, a man of European descent. I understood that it wasn’t really a commentary on race at all, but a critique of Western Civilization more generally — one made by someone in a position to see the sad truth: that we have fundamentally lost our way.

The evidence is overwhelming. Human-caused climate change is leading to more extreme weather, including more serious floods, droughts, and wildfires. Ocean temperatures are absurdly high, topping 101 degrees F off the coast of Florida recently. Plastic pollution is literally everywhere. The permafrost is melting.

Billions of animals are slaughtered every year for our consumption, most of them on factory farms. Not only do these creatures die brutal deaths, but their lives are filled with misery and suffering. This has prompted Yuval Noah Harari, author of the bestselling book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, to call industrial farming the worst crime in history. Meanwhile, up to sixty percent of wild animal populations have been killed off in the last half century and we are well into the planet’s sixth mass extinction.

Our metaphorical wisdom tablet isn’t just lost. It’s been pulverized, melted down and made into QLED television screens.

A Faulty Worldview

There are a multitude of factors that brought us to this point. Religious doctrines claiming human “dominion” over creation, extreme individualism, consumer-capitalism, and an undercurrent of reductionist materialism that renders matter spiritually inert.

The resulting worldview convinces us that we are apart from, and above the natural order, and that everything is a resource to be exploited or a product to be sold. Other creatures aren’t sentient beings in their own right, but merely fuel for our biological and technological appetites. The mountains and rivers exist not as sovereign entities, but as commodities to be used or traded. They are nothing more than inanimate objects. Stage props in a drama that is entirely about humans.

This is wrong. Tragically wrong, and it matters. Human behavior is shaped by our worldview. When we conceive of other-than-human beings as soulless objects, we will treat them that way. That’s why, while people have proposed plenty of innovative ways to address the climate crisis, to truly fix our broken planet we need a fundamental shift in our worldview — away from the commodification and objectification of the natural world, toward something more relational. Fortunately, there is just such an option readily available.

Animism

Animism is often defined as the belief that natural objects possess spirits or souls. It is a feature of many indigenous belief systems across the globe. In fact, anthropologists believe that our hunter-gatherer ancestors probably all practiced some form of animism, and that’s why it’s sometimes been described as the oldest religion in the world.

To call animism a religion at all is a bit of a mischaracterization, however. It has no polity or hierarchy. There are no set creeds. No scriptures. Animistic traditions we find around the world today share some common features, but each has its own particular beliefs and practices. They tend to be very local, based on the specific landscapes where they developed. That’s why it is better to think of animism more as an umbrella term, like theism or polytheism — a label that captures a general stance rather than a specific religion.

In other words, animism is a worldview.

For most of our time on earth, human beings lived in close relationship with the natural world. Our wellbeing depended on the ecosystem to sustain us — the plants and animals that provided nourishment, the wood and stone that gave us shelter, and the lights in the sky that helped us to track the passage of time. Animism was a natural response to this way of life. Other creatures, and even non-living things, were thought to possess sentience and unique forms of wisdom. The animistic view of the world was ultimately about relationships — a way of understanding humanity’s place in the complex, often perilous, interconnected web of existence.

Spider web

Though this way of thinking may sound foreign to modern ears, and though some at first may interpret it as superstition, there is nothing irrational about it. None of this requires giant leaps of faith. There is no need to invoke deities or subscribe to anything magical (though of course some choose to incorporate these elements into their personal spirituality). We’re dealing primarily in the natural here, not the supernatural.

Scientists have long known that ecosystems are formed by a complex web of connections. A growing body of research is expanding our understanding of consciousness in the non-human world. Elephants and dolphins grieve. Rats display empathy. Trees have methods of communication and fungi can problem solve. Animals are sentient and have feelings. This is no longer fringe stuff. In fact, some governments are codifying animal personhood into law and even granting rivers legal personhood.

In light of these discoveries, animism isn’t some ancient, exotic religion. It is a worldview that acknowledges basic reality — a reality that science is only now rediscovering. The world is not peopled by human beings alone.

This insight has profound implications. How would it affect the way we produce food if we viewed livestock as non-human persons and corn plants as sentient organisms? How would energy consumption change if we viewed natural resources as part of a living landscape?

A New Wisdom Tablet

These are difficult questions, and it may take some time to sort out, but a fundamental change in perspective will inevitably generate new priorities. It is painfully clear that a capitalistic paradigm based on endless growth and consumption is not sustainable.

Perhaps we can find guidance in the traditional ways of people who practice an unbroken line of animism going back to the distant past, the indigenous people who still retain some remnant of their metaphorical wisdom tablet. People like my Anishinaabe friend, who spoke of the sage and tobacco used in his smudging ritual as cherished relatives.

While we may gain valuable insights from today’s indigenous cultures, however, it is not ethical to coopt their beliefs and practices wholesale. They have already suffered generations of oppression and colonization. Their traditions are their own.

The good news is that each of us is rooted in the living earth — biologically and historically. Not only are we made of shared organic matter, but each of us, if we went back far enough, would find that we have ancestors who operated within an animistic worldview. This heritage is worth reclaiming. It’s not just a matter of remembering who we were. It’s about understanding who and what we are. We are members of an interdependent ecosystem, one peopled by a multitude of intelligent beings, and we evolved to live in deep relationship with nature.

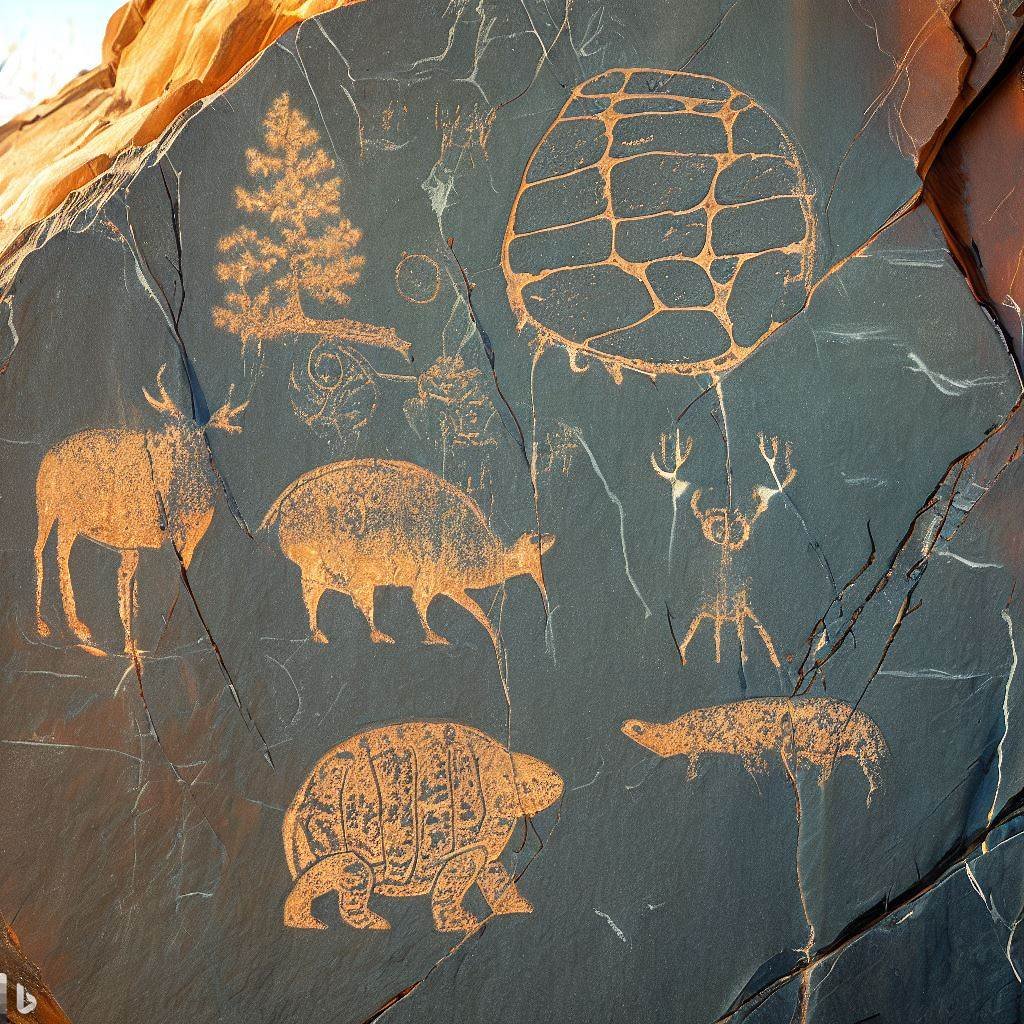

With this as our starting place, it’s time to sharpen our chisels and carve a new wisdom tablet for a modern world.